At CRREM, we originally used the term “Stranding Year” to describe the year in which a building’s current or projected carbon or energy intensity exceeds the respective CRREM pathway threshold. However, we believe “Stranding Year” is not an entirely accurate reflection of what performance against the CRREM Pathway measures or indicates, therefore we are moving forward with new terminology.

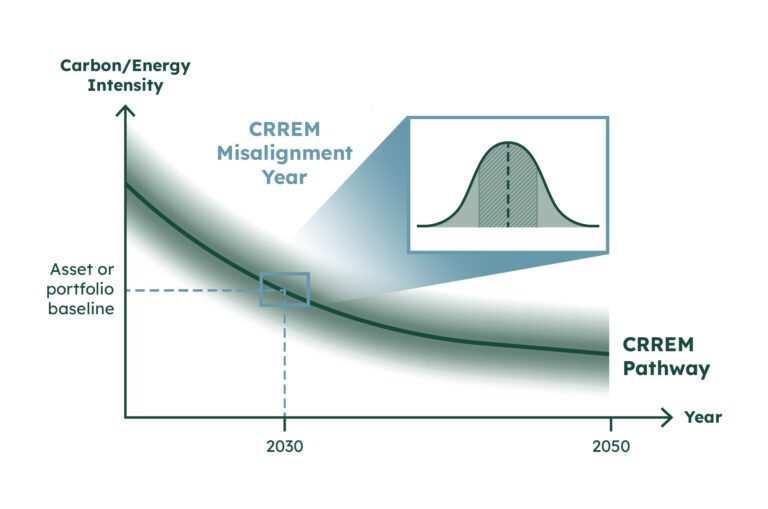

One of the core applications of the CRREM Pathways is to identify the first year in which a building’s carbon or energy intensity exceeds its allocated 1.5°C budget. Going forward, we will refer to this exceedance point as an asset’s “CRREM Misalignment Year.” While the data and methodology themselves do not change, this new terminology more accurately reflects what insight a CRREM Pathway analysis offers: a science-based early warning for investors and other real estate stakeholders. It does not conclude that an asset is or will become financially stranded. This is up to the market to decide.

“We believe the term ‘Stranding Year’ suggested a level of certainty about future financial outcomes that our science-based pathway cannot predict,” said Andrea Palmer, CEO at the CRREM Foundation. “By introducing the term ‘CRREM Misalignment Year,’ we more accurately communicate what our pathways measure: misalignment with a certain climate scenario, not a definitive loss of asset value.”

A key concept frequently associated with transition risks in real estate is that of the stranded asset. Originally shaped by the Carbon Tracker Initiative, the term stranded asset describes an investment “which, at some time prior to the end of its economic life, is no longer able to generate an economic return, as a result of changes in the market and regulatory environment.”

Assets become financially stranded only when markets recognize risks or known impairments by underwriting higher cap rates, declining rents, reduced liquidity, or other forms of pre-mature write-downs. Climate transition risks are a major driver that can lead to an asset becoming stranded, but exceeding a carbon or energy intensity budget does not automatically mean the asset is or will become financially stranded.

Real estate, as a physically immobile yet adaptable asset, typically maintains some residual value. Properties that face market- or regulation-driven impairments can often be repositioned through retrofitting, repurposing, or other value-added strategies. Reflecting this complexity, we want to steer the global real estate industry towards a more nuanced assessment of transition risk (and opportunity). Buildings that are misaligned with the CRREM Pathways (i.e., CRREM Misalignment Year has already passed) can still be attractive investment opportunities if (1) markets are not appropriately pricing-in transition risks, or (2) the asset has a credible transition plan in place. Of course, we prefer the latter.

The CRREM Misalignment Year is an early warning system and important piece of information to help investors identify transition risks in a globally standardized way. However, just as a portfolio manager would never look at one key valuation metric in isolation, we also encourage users to complement the CRREM Misalignment Year with additional asset-specific and market-based analysis for a more comprehensive view. We believe it is essential to place an asset’s CRREM performance within the broader context of local regulations, tenant demand, lease structure/length, and capital market conditions, as well as how the asset itself differs from the market average.

The CRREM Pathways reflect the market average of a given asset type and country/region. While building performance data is not typically normally distributed, it is important to demonstrate that the CRREM Pathways reflect a range of values (see illustration below). Building performance can deviate from the CRREM Pathways for a number of reasons. For example, when a building has atypical usage patterns or design.

Student accommodations are a common case. Due to their hospitality-like features and more densely-designed floor plans, these assets generally have higher energy intensities than traditional multi-family, apartment buildings. An office building with 24-hour trading desks or other more intensive tenant activities will also have higher energy consumption than the average 9:00-to-5:00 office building.

This contextual information adds important enrichment to a CRREM Pathway analysis, and supports investors with making a more complete transition risk evaluation. It’s not black or white; some deviations are expected and explainable. Investors should aim to distinguish between design- and usage-based deviations, like the above, and performance-based deviations that reflect an underinvestment in building efficiency. This context turns isolated CRREM results into meaningful transition risk assessments.

Referring to the primary CRREM indicator as the “CRREM Misalignment Year” is clearer and more objective:

The change aims to enhance clarity, nuance, and constructive action, rather than dilute urgency or reduce accountability. We feel “Misalignment” more accurately reflects the continuous nature of transition risk and encourages engagement and improvement rather than binary labeling, which can lead to defensiveness or greenwashing by omission. We see this change as providing a more actionable and strategic lens, acknowledging that decarbonization is a dynamic journey, not a one-time event. The concept of “misalignment” still signals risk, but does so in a way that resonates with investment-grade audiences seeking forward-looking solutions to come back into alignment. CRREM’s credibility comes not from the severity of a term but from the rigor of its science-based pathways, which are unchanged.